Blog

Comedy Extracts

From the Comedy That Wasn't Funny to Studio 8H

Isn’t there an old saying that’s something like, “If it takes you a while to explain a joke, it’s probably not funny?” Did I make that up? I’m not sure. But I think there’s truth in it.

This is why Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, which delivers (via firehose) a three-part epic in about 600 pages, is objectively … not funny.

The dense work that explores hell, purgatory and paradise is philosophical, theological and political … but comical? Not so much. It’s unlikely that Tina Fey circa 2002 could produce so much as a pity laugh with the content that was jammed into 100 cantos in the early 1300s.

The title worked then when the word “comedy” referred to a happy ending, but to the modern reader, it’s a head scratcher, leaving the lector asking, “Did I miss the joke?”

No, but if you’re not careful, you might miss the thin thread that actually does connect The Divine Comedy to your all-time favorite SNL monologue.

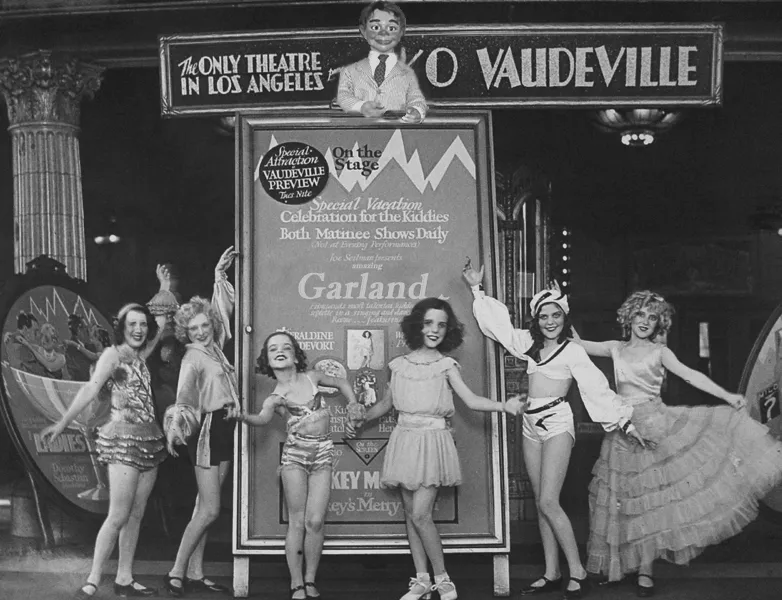

If we fast forward to the late 1800s, comedy evolved again. Instead of discourse on politics and religion, comedy became this sort of fast-paced, slapstick form of entertainment.

Dante exits stage left … and Vaudeville enters the limelight.

Vaudeville

This form of live entertainment revolved around witty one-liners and crowd-pleasing humor that wasn’t shrouded in deep, intellectual layers. It was simple, surface-level and really just silly. When you think Vaudeville, think of a performer slipping on a banana peel, and the crowd buckling over with hysterical laughter. Peak comedy as we know it today? Absolutely not. But consider the era. People were after a mental escape—especially those middle class folks who couldn’t afford a night at the opera but needed some sort of reprieve from navigating industrialization and the financial and political uncertainty that it created. What could be more therapeutic than the joyful chaos of humor in its most simple form after a day spent completing monotonous factory work?

Now, whether or not the next evolution of comedy spawned from a meeting of Vaudeville performers or just naturally, based on the mere fact that humans love to hear themselves talk, is a little unclear. But over time, the slap was sticking less, and the monologues got more meaty. By the early 1900s, solo performers were storytelling live on stage.

Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome … stand-up comics.

Stand Up Comedy

The connection between storytelling and stand-up comedy is clear and often blurs lines to this day. Equally as important as the story or the bit, is the timing. And we can credit the perfection of comedic timing to one of the earliest stand-up comics, Jack Benny. Benny, from the 1930s-1950s, set the standard when it came to not just what you said as a solo performer, but how you said it. We can also credit him with introducing self-deprecating humor … although he probably wouldn’t accept the praise. Not on brand.

Today, whether at Rockefeller Center in Studio 8H or in your humble local improv theater, students of comedy are, whether knowingly or unknowingly, paying homage with their handwritten bits to the performers who came before them. The ones who were offering a reprieve from the early days of American urbanization, the Great Depression and the post-war era. And if you follow that funny thread back far enough, their last bomb on stage (a rite of passage, of course) had a little something to do with the most unfunny story…The Divine Comedy.