News

Marketer Magazine: On The Record: Conducting Strong Interviews with the Media

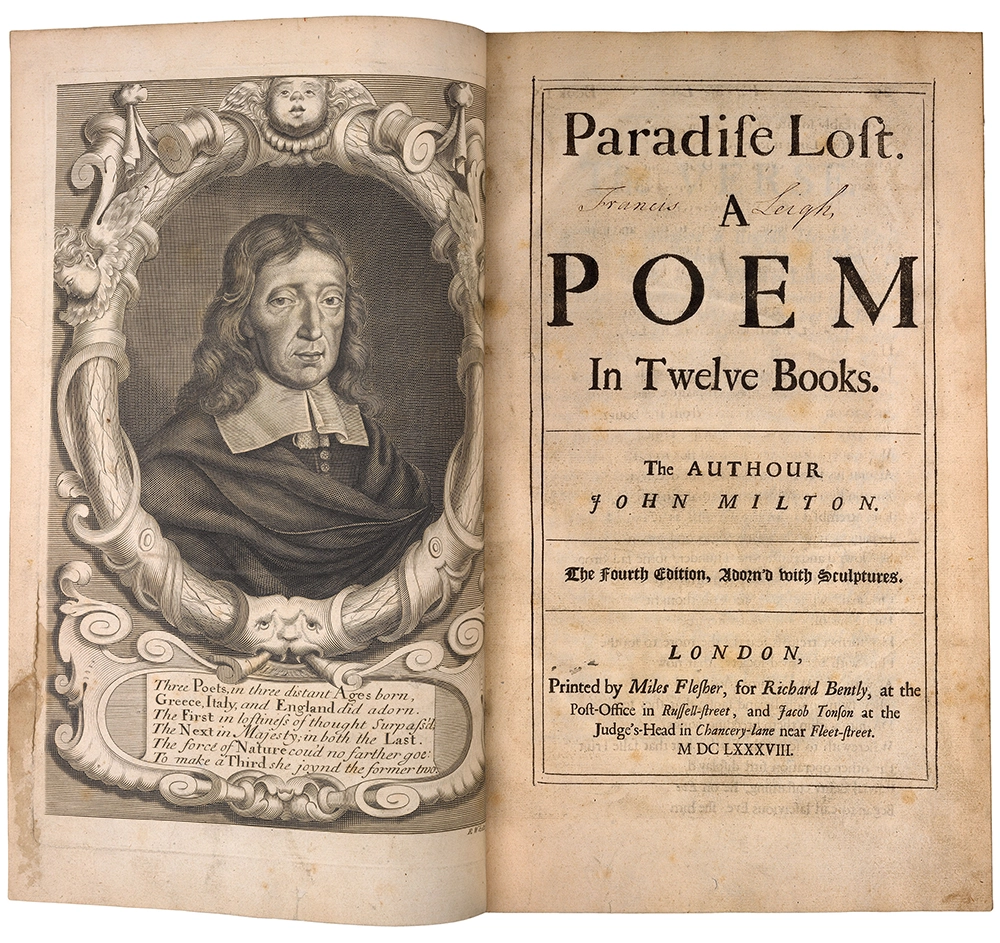

Madness in the Margins: John Milton’s Paradise Lost and the Cost of Meaning

Of Man’s first disobedience, and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful seat,

Sing, Heav’nly Muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That shepherd, who first taught the chosen seed

In the beginning how the heav’ns and earth

Rose out of Chaos: Or if Sion hill

Delight thee more, and Siloa’s brook that flow’d

Fast by the Oracle of God; I thence

Invoke thy aid to my advent’rous song,

That with no middle flight intends to soar

Above th’ Aonian mount, while it pursues

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.

(Excerpt from Paradise Lost, 1658-1665)

Ten thousand lines. Ten thousand lines of perfect cadence, syllable structure and word choice. Milton agonized over etymology in his seven-year endeavor of writing…or, narrating in his case, Paradise Lost. There’s an irony in imagining Milton, suddenly blind in his 40s, brilliant and deeply convicted by his own words, being driven mad in the process of creating his life’s work. His epic poem, Paradise Lost, gave us an understanding of divine rebellion, but it came at the sake of his sanity.

Literary critics and historians have long speculated about the toll Paradise Lost took on Milton. We know that he was blind, grappling with political disillusionment and battling existential crises, one after the other, protected by only a desk and wielding only a “proverbial” pen. You see, Milton narrated Paradise Lost to his daughters and other various scribes, who then transcribed his poem. Every syntax dilemma, every dive into etymology, every counted and recounted syllable traveled through Milton’s mind, out of his mouth and through his devotees, until it eventually, painstakingly, landed on paper.

Through meticulous verbal edits, each word had to fit perfectly, not just in meaning but in sound, rhythm and theological understanding.

Like an architect more than a poet, Milton was parsing through syllables, as if they were building blocks ensuring perfect meaning and context but also a poem so satisfying to the tongue, it feels as though no other combination of words could exist. This precision came at a paradoxical cost. Paradise Lost is a poem about redemption by a man who damned his own equilibrium in its creation.

The paradoxes continue within the poem itself. Milton, driven by the insatiable thirst for perfection, mirrors Satan — the antihero whose character arch displays a quest for something that rivals the divine. Milton eventually succumbed to wearing his humanness, that is to err, as shamefully as Adam wore his nakedness in the poem. But ultimately it’s the humanness that makes Paradise Lost such a masterpiece. Beyond the ten thousand lines frozen in time is the understanding that underneath each line are layers of obsession, pursuit, drive, flaw and failure, and many of the darkest corners of the psyche.

Maybe Milton knew then what he wanted us to garner from Paradise Lost.

What good are ten thousand lines without the conquest of arriving at them?

What good are words without their meanings?

And what good is redemption, without first a little rebellion?